I’m fairly aware of my relationship with money. I’m less aware of my relationship with craft. But I scarcely know where to start once class becomes involved. It’s tricky with any mending. With sashiko it’s near impossible.

Sashiko is a style of functional embroidery developed in Japan. Patches are applied to cloth with decorative geometric stitching. In essence it’s a form of patchwork that can be used for both strength and ornament. It is also one of those topics that if I think about too long my head begin to spin. Like standing in a hall of mirrors.

A quick bit of history: sashiko arose out of necessity and was developed by the peasants of feudal Japan. For centuries, sumptuary laws divided Japanese society into strict categories of fashion. Farmers, day laborers, and servants were restricted to plain cotton and linen only, dyed in solid colors. Dressing outside the sartorial proscription of one’s class was deemed a threat to social stability, and a punishable offense. In 1681, shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi made an example of the merchant Ishikawa Rokubei, stripping him of all property and banishing his family from Edo because – in Tsunayoshi’s estimate – Rokubei’s wife was dressing above her station. Far too similarly to the fashions of the wives of Daimyo, that is the lords who were outranked only by the emperor and shogun. What was a merchant’s wife doing strutting about in such finery? What disrespect to order! And to think Shogun Tsunayoshi might have spoken to her as a near equal. Oh, how embarassing! Such vulgarity could not be allowed to stand.

And so we know this story because of how thoroughly Rokubei’s own peers took note, lest they too lose their business. Merchants toned down the extravagance of all outward costume, placing the ornament inside of the garment instead. A rather plain colored kimono, for example, might have an elaborate lining, viewable only in private. Or while engaged in negotiation or casual chitchat with a fellow member of one’s class, a merchant might loosen their collar, or turn up a cuff, to reveal a rich and lustrous silk, otherwise concealed, as if to say, ‘Now now. Let’s not pussyfoot about. I may not be able to kill you myself. But I can easily afford twenty men who could.’

I love those stories. Spare me sword fights and samurai. Honor bores me. Tell me more of intrigue over tea.

Concurrent to this period, from 1639 to 1854 Japan was under self-imposed isolation that prevented goods from entering the country from abroad, which put cotton in short supply, and a peasant’s wage has always been just that. So anyone who had any cotton kept every bit for as long as they could, patching wherever the cloth turned thin.

Then – just as the merchants found their own work around – some clever bumpkin of the toiling class realized that sumptuary laws only prohibited patterned fabrics and said nothing at all about patterned stitching. Now with sashiko even a pig farmer could create and wear ornate and striking clothes without breaking any law. And – unlike merchants – could do so openly. Afterall, it wasn’t made of silk. Sashiko was only solid colored cotton on solid colored cloth accentuated with the cheapest material available – thread – itself made of cotton or ramie, a type of wild nettle. It wasn’t as though the Shogun strolled about in sashiko, and merchants wouldn’t be caught dead in the stuff, as it quickly became associated with the borderline destitute. (Thrift may be admirable, but poverty has never been in fashion.) Sashiko was a way to skirt a prohibition with the minimum of tools and cost. A sly rebellion against sartorial edict. It’s quite punk really.

I’m not Japanese, and class structure in America is nowhere near so rigid as it was in Edo era Japan, but I likely have more in common with an Edo-era peasant than either he or I have with the leaders of our respective times and nations. Which is why I feel so conflicted whenever I sell a sashiko piece, not because of my ethnicity, but because of my income. I almost never sell to anyone of my own social rank.

With the exception of the very few and treasured luminaries, artisans of every era have always been among the lowest class. On career day, hardly any grade school child is ever guided towards the arts. I say that as an artisan myself. True, I may have a number of middle-class characteristics (college degree, no debt, run my own business) but by sheer metrics I am and have been decidedly lower class ever since entering adulthood some twenty years ago. I have always rented, have no car, never earned more than $35,000 in a year, and have a present annual income around $25,000. Above the federal poverty line of $14k/year, but by the local standards of the San Francisco Bay Area, extremely low income.

So sashiko is definitely for people of my own financial bracket. But I almost never sell to anyone of the modern peasant class – fruit pickers, grocery store clerks, baristas, Amazon delivery truck drivers. These people generally don’t come to me for the understandable reason that they can’t afford my rate of $25 an hour. I don’t blame them. I couldn’t afford my own service if I had to pay for it, which is partly why I learned to do it.

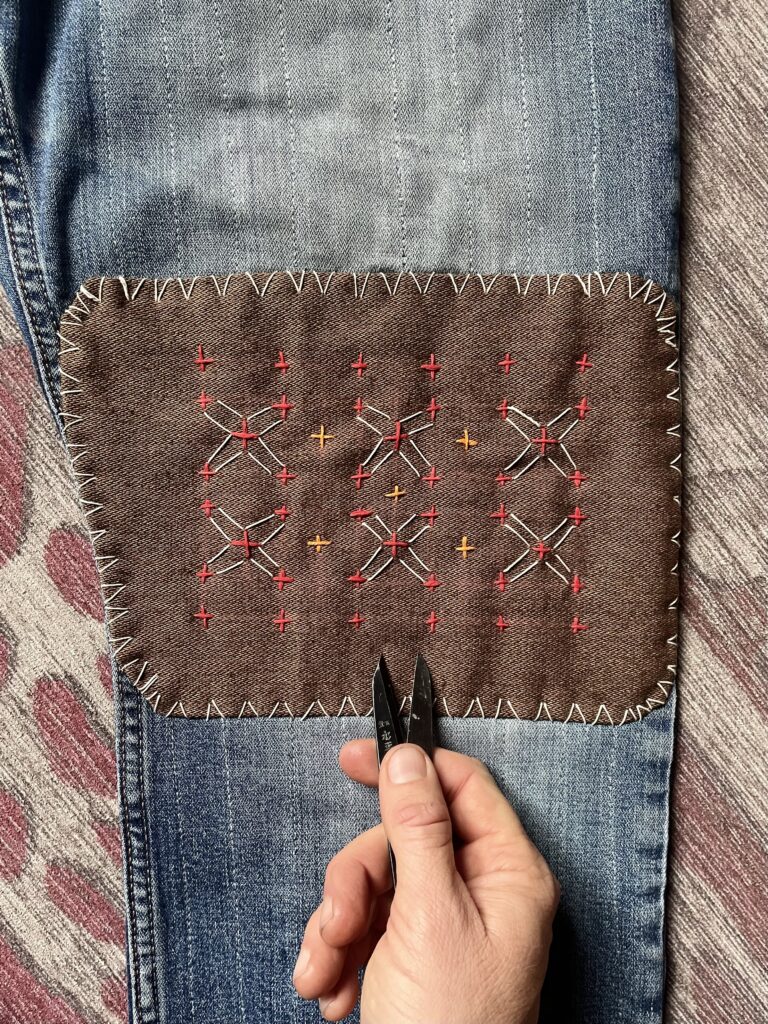

I do not now and never have defined my own interpretations of sashiko as “authentic” in either make or pattern – for starters, I mostly work on blue jeans and no Edo era peasant ever wore a pair of Levi’s – but I do try to be authentic in spirit. Blue jeans are to the modern laborer what the boro kimono was to the Edo period. And having grown proficient if not yet professional in a traditional peasant craft, it sends me spinning into self-doubt and suspicion of class treachery knowing that the people who can most afford my services generally hail from a much wealthier tax bracket. Perhaps these customers could never make a pair of pants, but they could easily buy twenty.

A small story of my own; some months ago a customer asked for some sashiko on a pair of jeans and at the collar of a Loro Piana shirt. The name didn’t mean anything to me, and I was pleased but not especially taken by the work that I neglected to take a photo. The customer was extremely happy with the result that they then came back with another pair of pants and another Loro Piana shirt, at which point I looked up the designer and found the shirts retail for around $800 apiece. I did the work to both my and the customer’s satisfaction, but I felt somewhat uneasy about it, as though I had misapplied or exploited a tradition of thrift and ingenuity for the personal gain of $25 an hour. I don’t believe at all that the customer took advantage of me – I went willingly – but I feel like I’m the one who betrayed the craft. We have a word for this in English. It’s called being a sellout.

And so, just as those who are most able to afford my service are the most likely to wear it, the previous class indication of sashiko has become completely reversed, or at least irrelevant in this transported context. (A friend sent me a link to a sashiko workshop in nearby Marin county, where tickets to learn directly from the artisan were selling for $150 per student per class. This is the same amount I get paid to teach a two hour class, and for which students themselves pay $50.) Like oxtail soup and whole grain bread, something that originated in peasant necessity has become fetishized as an aristocratic luxury.

But there was also the part-time bartender who saved his tips for a week to be able to pay me to touch up two of his jeans (it took 3 hours a pair, so $150 all together). Or the local café owner who, every time his own pants need a touch up, pays me half in cash and half in store credit – so roughly $75 liquid and another $75 in sandwiches. (You can see photos of the pants from both these customers included in this post.) These exchanges are far more satisfying. They feel truer to the spirit of the craft, even though in every scenario – whether on an $800 shirt or an $8 pair of pants – sashiko is still about extending the life of the garment.

I don’t know if I’ll ever have the answers I need to feel completely at peace with the craft. Not as long as I’m charging for it. So it’s likely a paradox I’ll just always have to manage, since I can and do charge money for my skills, and as I continue to improve those rates are never going to go down. Cost of living certainly won’t. Sashiko may have started as a peasant’s craft, but it requires too much skill and focus to receive only a peasant’s wage.

But if even a peasant’s wage is too much for your present budget, I get it. Been there. (still there.) I do teach classes in sashiko at the East Bay Depot for Creative Reuse, or you can send an email through my contact page about arranging a private lesson. This might be more money up front than a single piece of sashiko would cost, but it would give you the skills and tools to put some sashiko in your own wardrobe yourself. (“teach a man to stitch…”) And of course I’m always happy to discuss mending your own clothes for you – with sashiko, or with some other skill.